The Mandala Connection

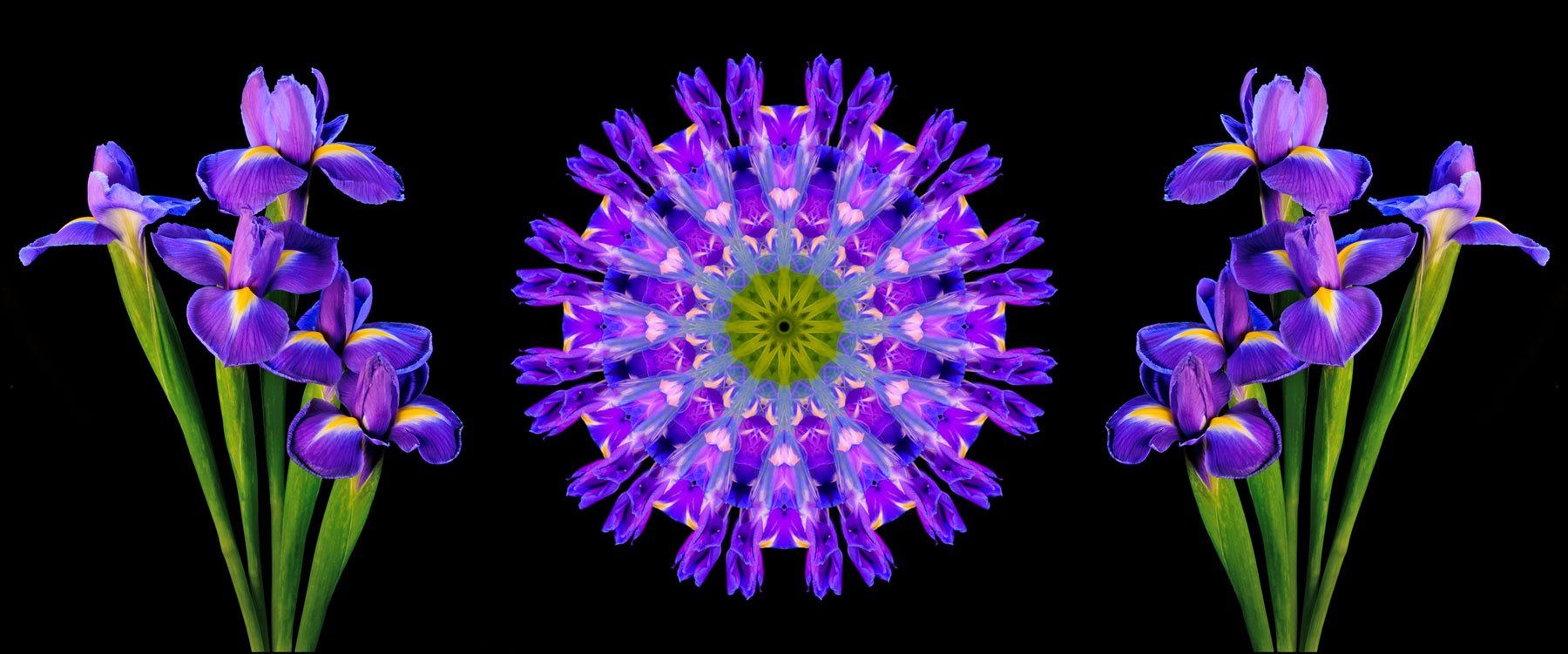

I have always been fascinated by mandalas. When I was young I loved the mandalas that were a gift from nature. I would gasp in awe at the dew on a spiderweb; fascinated by how the tiny droplets captured the light and celebrated the beautiful patterns and shapes. The delicate design industriously weaved overnight by the spider. I loved the rhythm of the pattern. I found mandalas everywhere in nature’s playground. So many flowers but in particular I was intrigued by the yellow daisies, which popped up in our lawn. The ones you would hold under you chin to see if you liked butter. I would examine this flower with great intrigue. The beautiful petals bordering the intricate floral disc. A mandala of joy.

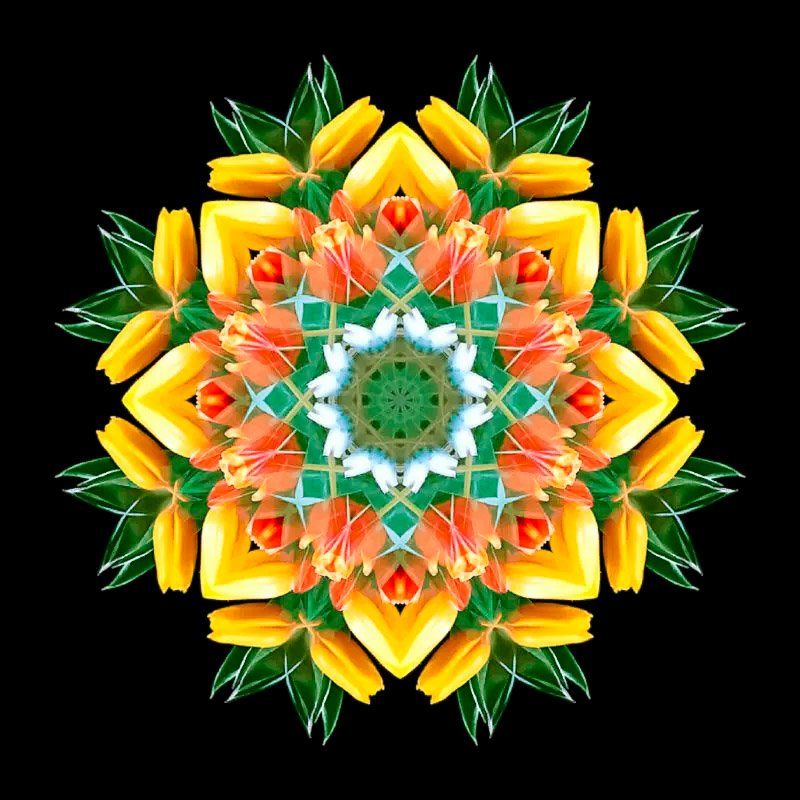

Tulips from MOODLAPSE

Man-made mandalas were also there for me to admire. The mandala of the paisley pattern in the material mum bought to make a dress for me and my sister. Mandalas in mosaics in pots or tiles in a friend’s garden. My favourite, the mandala of the kaleidoscope. I would hold that little tube up to the light coming through the lounge room window and I would turn it in circles against my eye, completely captivated by how the shapes would change from one mandala to another. I would move my head in circles with the kaleidoscope in position and be filled with such joy watching the merging of mandalas, the colours changing, the shapes changing. I would take it outside and point it to the sky and against my skin or clothes, where I would be filled with delight as the mandalas in the kaleidoscope took on the colours I was wearing. I had no idea how it worked, but that didn’t matter. I enjoyed it without having to know the science behind it. I loved the kaleidoscope for what it was. And I loved the experience even more because of the mystery and mysticism of that little tubed instrument and its mandalas.

Of course, I didn’t know they were called mandalas back then. I was just in love with the shape and patterns, and how they made me feel. It wasn’t until I went to university that I discovered the term ‘mandala’. In our literature class we would analyse poetry, classic novels, modern literature and children’s books using the ideas of the great philosophers of our time. I was introduced to Taoism, Calvinism and Freud. We unpacked traditional and modern feminism. And I discovered the writings of Nietzsche and Jung, and found a deep connection to both, which I have carried with me ever since. I saw similarities in the models of the human psyche these philosophers wrote about. Neitzsche’s concept of the Apollonian and Dionysian (form and chaos, light and dark, masculine and feminine) seemed to be echoed in Frued’s concept of the superego (our preconscious moral guardian) and the id (unconscious energy working to satisfy our basic urges, needs, and desires). I saw parallels between these concepts and Jung’s archetypes the Anima (feminine part of the psyche in touch with the subconscious, an archetype of illusion) and the Animus (masculine part of the psyche, an archetype of reason). Importantly, I saw parallels between all their work and the ideas which came before them, the beautiful symbolism of Taoism’s Yin and Yang. Ancient Eastern philosophy found in modern Western philosophy and psychology. And it was all about dualities. It was all about symbols and archetypes. I became a bit of philosophy geek. It was all I talked about. I became quite boring at parties.

According to Jung, the mandala is the ultimate archetype. The ultimate universal symbolic pattern to explain the nature of the world and life. The ‘psychological expression of our total self’ and a symbol of our collective unconscious (our inherited unconscious). He believed that we see them, dream of them and have the desire to make them when we are going through a period of personal growth. Jung would draw them, and so would his patients, linking their conscious self with their unconscious self to gain insight into their lives. In his words, ‘we know from experience that the protective circle, the mandala, is the traditional antidote for chaotic states of mind.’

‘Mandala: The basic pattern of the psyche which spins from itself the web of life'. Dictionary of Symbols, Tom Chetwynd

The mandala is our connection to our true selves, our authentic self. The mandala is our collective unconscious, our primordial being, our mythology and connection to each other. The mandala is everything, nature, the world and the universe. Jung, in describing one of his mandala drawings, articulates this beautifully as: ‘the microcosmic enclosed within the macrocosmic system of opposites’.

The mandala is a cosmic diagram of the relationship and the interaction between the individual, the collective and the world. The mandala works at a higher level than our conscious self. It taps into all parts of our unconscious self, while simultaneously connecting us with the universal memories and impulses of humankind, alongside all that nature is and can be.

It should not be of any surprise then, what I discovered as I started writing this piece. As I wrote my introduction about my fascination with mandalas in nature as a child and my love for the yellow daisy, I paused to reflect on my relationship with mandalas. My eyes rested on my web banner. And I laughed as I saw for the first time a deeper meaning in the image I had chosen long ago. Before now, I have always held my attention on the motif of the hummingbird (a symbol representing my curiosity). And in doing so, I hadn’t noticed the significance of the flower in that the image. The image I had chosen to represent curious muse was not only of a hummingbird, it was of a hummingbird with its beak in a yellow daisy. My mandala of joy.

Of course, I had done this without even knowing I had. Because writing for me is about those two things: curiosity and joy. In picking this picture my conscious self was focused on the hummingbird, while my unconscious self was focused on the daisy. Our experience always comes to light through archetypes. Today my conscious self became aware of my unconscious decision making, and aware of perhaps a universal energy at play in that decision. Because, the decisions we make each day are driven by a deep force. And this is what the mandala represents. It is a visual diagram of the energy of our individual conscious and unconscious selves in harmony with the energy of the mythology we carry within us, and the energy of the world around us.

Jung describes the mandala as the archetype of transformation. He sees mandalas as ‘birth-places, vessels of birth in the most literal sense, lotus flowers in which a Buddha comes to life. Sitting in the lotus-seat, the yogi sees himself transfigured into an immortal.’ Of course, as his own words suggest, the mandala existed long before Jung.

The word ‘mandala’ comes from the Sanskrit word for ‘circle’. In Buddhism the mandala is the path to enlightenment, representing the transformation of the universe and also an individual’s journey of growth. Mandalas capture the cycle of life, the wholeness and connection in their circular design. At the same time, mandalas represent the infinite parts of our inner and outer worlds, and their relationship, through the complexities and repetition of pattern.

Mandalas are also used as meditation aids like the yantra in Hinduism. Similar to the mandala, the yantra, is a circular patterned symbol used in Hinduism for meditative rituals. A less complex visual, the yantra, according to the scholar, Khanna Madhu, functions as ‘a symbol of cosmic truths and as instructional charts of the spiritual aspect of human experience.’ The yantra, like the mandala, is the relationship between the inner and the outer worlds, the microcosm and the macrocosm.

People use mandalas to meditate, and mandalas come to us when we meditate. Studies have shown that colouring mandalas change our brainwaves to help us reach a relaxed state with reduce anxiety. This shift in brainwaves is also evident when we visualise a mandala. According to an article in Times Union when used in meditation, ‘Mandalas have been shown in clinical studies to boost the immune system, reduce stress and pain, lower blood pressure, promote sleep and ease depression.’

Regardless of the meaning human-kind has placed upon the mandala, and our use of such a symbol, nature has been creating mandalas since the beginning of time. Many fruits hold their seeds in a mandala pattern, the shells of animals a mandala, as is the sun, the rings of trees and the pattern of snowflakes. Mother nature’s mandalas are her life source. In its simplest form, the mandala of the flower attracts birds and insects to feed from its nectar, and for those very small insects, the mandala is a resting place while feeding. The flower’s mandala nourishes those that visit keeping them alive, and the symbiotic relationship is complete as those that visit the flower, transfer pollen via their bodies or bills and fertilise the plant. Helping the plant to grow and reproduce. Nature’s mandala is the centre of life for all, the animal and the plant.

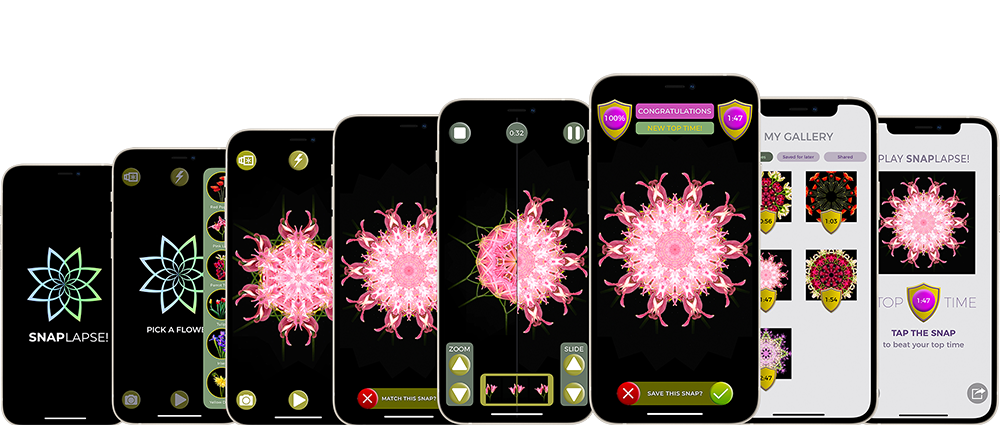

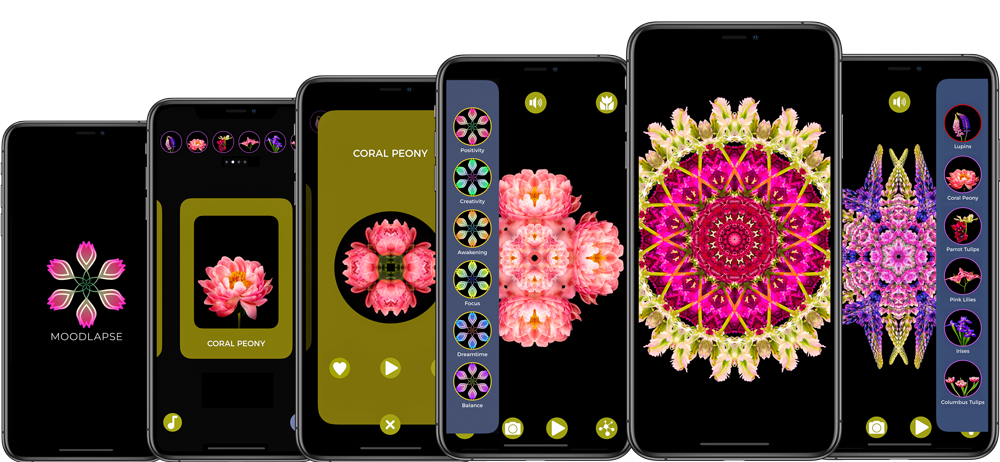

This is probably why I was so drawn to the mandalas created by Moodlapse. A relaxation app created by Tim Platt. A mesmerising digital kaleidoscope created with flowers. They are so amazingly beautiful and calming. I have admired and enjoyed Tim’s creations for some time. You simply choose the flower you like, select it, choose an audio track and watch and build mandalas by tapping and swiping the screen. You can track your time, get information about the flowers and create an endless number of moving mandalas. It filled my heart with great joy today to see that in the middle of everything that is going on at the moment, Tim has generously offered this app for free. Providing everyone with an indefinite free trial, his gesture to help ‘calm anxiety and accentuate positivity at this difficult time.’

Jung said, ‘Mankind always stands on the brink of action it performs itself but does not control’. And here we are. True to his words. Standing before what we have created but cannot determine. The world burns when there is collective anger. The world has disease, when there is collective dis-ease and sadness. The truth shared by many including early Italian Renaissance philosopher Marsilio Ficino, that ‘the whole universe is one living being’.

Such an important reminder. We all have a part to play in the wellbeing of the whole universe. We all influence the wellness of its body containing the species of all things. We are all responsible for the health of the world’s soul, including our archetypal mythology. It is up to us to care for the spirit of the universe.

The world’s soul hurts when species are collectively hurting. When we are spiritually broken, the spirt of the universe is broken. And conversely, we experience great challenges in life when the world’s soul is hurting and the spirt of the universe broken.

There is such beauty and mysticism in mandalas. There is also universal healing. I could not encourage you enough to pause and notice the beautiful mandalas around us, which nature has created. And to feel the joy of them. To create some collective and universal positive energy. Mandalas are everywhere: in the constellations of stars, in the shells on the beach, in the flowers in your backyard and even in the patterns of soap suds. But most importantly, there are mandalas inside us. And they make us who we are, in the design of our eyes, the spirals of our fingertips and at the very biological centre of our being, our cells. And although we are unique individuals, we are all in this together.

••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

About Kristina Garla

Kristina lives in Australia and has worked as a writer in the field of marketing and communications for nearly 30 years, across a number of industries including education, health, charities, human rights, finance and the arts. At work she brings the art of story telling to strategy, campaigns, marketing and communication plans, editorial for collateral or web, media releases, and more. At home she writes poetry, plays, short film scripts, blog posts, social media posts, lists, letters, reflections, cards, short stories, children books, notes, a novel, a non-fiction book, speeches and memoirs.

Visit her amazing blog at: Curious Muse

Learn about her online meditation classes at: Meditation Muse